Monopolies -- Baseball, Topps, and America's Rise out of WWII in the 1950s

00:00

So the concept for this episode is monopolies within monopolies within monopolies.

00:21

It's to talk about American political power in the birth of the 1950s Topps sets. The idea here is you have a couple of different things that happen around the mid-50s. And I'll couch this by what happens that actually births the modern baseball card in 1909 with the T206, and the monopoly that happens with American Tobacco. And the antitrust suit that breaks it up.

00:51

This is 1911. They quickly crowd out the market because of their automated cigarette roller that they bought from a worker from a rival company. They bought out his innovation and they quickly dominated the market just because they could produce cigarettes faster, faster, faster, quicker and quicker — with better quality as well.

01:20

The whole antitrust thing happens at the onset of the 20th century with a lot of the industrial things that happened in the country at the time. There's this increased technology and people start to corner market shares. This is JP Morgan, the Rockefellers, Henry Ford. There's this massive industrial revolution that's occurring in the country. So you have a political moment where

01:48

industries are becoming monopolized by superpowers, super industrial powers. This is not just limited, of course, to the nation of the United States. This is becoming a global political problem. So this goes into World War I, World War II. And what happens after those two wars, you basically have a bookend, historically, right? The historical bookend is 1909, the Dead Ball Era, the T206. And then you have this massive world war and then another massive world war immediately afterwards.

02:17

And then you come out on the other side of that bookend in the 40s, 50s. So this is where it gets fascinating because it's almost like there's an immediate bridge that occurs from the T206 innovation, which is directly connected to American Tobacco, which is a industrial superpower of tobacco production, the primary cultural enjoyment of the entire American country. Cigarettes are just absolutely huge and they're huge until...

02:46

even going into the later part of the 1900s. You have that on one end, World War I, World War II, and then you have this emergence into an era where America has essentially monopolized the world global stage. It's no exaggeration to say after World War II that America has, in many ways, almost conquered the world. I want to allude to Alexander the Great and his historical project. You almost have

03:16

that is what happens at the end of World War II. America emerges clearly not only on the side of the victors, but perhaps as the chief victor itself, and with all of the political power and might that comes with that in terms of resources; its international constituents — whether those are pseudo colonies or just political cedings of power that are occurring around the globe to America after that war.

03:47

This is when you have a monopoly within a monopoly within a monopoly. You have the monopoly of American world power. You have one of the only monopolies that's actually ever been allowed in America — maybe actually the only one. I'm not sure. That's not my area of expertise — but Major League Baseball, right? This goes back to what I was talking about with the Federal League and the whole antitrust suit that happens with the Federal League a decade after the American Tobacco antitrust suit where ATC gets broken up

04:16

and it gets turned into, the Reynolds cigarette company and there's a bunch of other ones. You can actually still see a lot of the old American tobacco factories in North Carolina and Virginia. They're all still there. Some of them have been converted into apartment buildings and things like that. A lot of them are. But anyways — you have monopoly within monopoly within monopoly. The MLB wins that antitrust suit and it's a legal monopoly, which is just insane, right — against the Federal League. The Federal League is saying that

04:47

MLB is making it impossible to hire players because they just buy them right back. The courts are almost declaring Major League Baseball a privately owned national park — is almost what happens. It gets declared America's pastime as an institution, but there’s obviously private ownership power there that you can see to this day. It’s a legal private public institution. Some of the richest people in the country own these baseball teams.

05:14

So you have one monopoly, America, the world power, emerging after World War II. This has essentially monopolized the global scene and you see a lot of the stuff that occurs afterwards in terms of the prosperity of the country stem from this spoils of war… which is very brief because of how the political and economic situation is handled, it's almost an embarrassment of riches and the country squanders it due to just flat out poor management. So you have that. Then you have another layer,

05:40

which is Major League Baseball, as we discussed. It's a legal monopoly as of the 1920s. The Negro Leagues get ceded into that. All the Federal League stuff including Wrigley Field gets ceded into that and it's over. A lot of the best Cuban players, Venezuelan players, Puerto Rican players, they all come to the United States as well as Japan, elsewhere — in and by the 1950s onward. This is something that is and gets set into motion by the larger political and economic circumstances of the globe at the time. And then within...

06:10

that monopoly of the MLB — reified and redoubled upon integration in 1947 — you have another monopoly, which is Topps baseball cards, right? The 1950s and 60s sets. Topps buys up Bowman at the beginning of the 50s, middle of the 50s, and it turns into this monolithic cultural product. This is where it gets really interesting, right? Because you can say that due to the utter singularity of these monopolies, they're almost public institutions that are owned privately. The Carnegie family owned entire towns outside of Pittsburgh at this time in history. You’re talking about a region. Stores, land, the very infrastructural grid. This is an interesting economic concept because you have a lot of

06:39

economic and political ideologies that you could gesture to out of laziness, but when you have that level of cultural monopoly of product as in Topps or as in Major League Baseball post-integration — which is crucial — you have players from all over the world coming to play in this league. It's almost in the way that the Smithsonian is a cultural product which is both privately and publicly backed. It's an institution

07:09

of culture and of humanism. But in the case of baseball, it is in the most part a monopoly of private interest; Topps reflects this. So I really want to set that stage and establish that because if you look at things through that framework, you have the institution of Major League Baseball and the institution of Topps. Topps is the sort of, you could call it like the White House painter or the national painter, so to speak. It's the

07:36

representative image making institution that creates the cultural object, or product, to sum up and distill the cultural ambiance of the essence of the public institution of baseball itself. And this is really powerful because if you contextualize things this way — I was thinking about this in terms of the history of baseball, the full history of it. It's something that

08:04

could never truly be told because there are the roots of so many different interweaving stories, both national and international. It's such a broad thing that it's more of a poetry than it is a history, because you could never truly sum it up. Even when you look at someone like Dizzy Dean or Satchel Page, there's such a mythic full history of that individual. Dean’s childhood, Paige’s childhood. These are absolutely essential American historical moments and developmental phases of figures who paint the picture of America’s soul through their lived experience. That mythic full history of the individual intersects with a large, large, large

08:33

public denomination of people who are experiencing the legacy and the legend that's playing out on the public stage. It’s almost a massive spiritual church of baseball — where the mythic world historical and the intimate personal as forces of identity collide. That is the Gashouse Gang of 1934 in the midst of America’s economic plummet or Satchel Paige with the Monarchs, as he enters the major leagues; goes down to play in Cuba. Dizzy and Paul Dean working on the cotton field, throwing hickory nuts and practicing their pitching skills. So you have this very, very, very broad mythic tree, right? With branches and roots that reach far beyond that which

09:00

any one historian or even an institution of history could ever possibly sum up. There's the experience that many individual people have through that. Our personal experience as a collective unity of baseball. Someone told me this experience that they had of walking through a neighborhood and there was no AC at this period of time — everyone was playing the baseball game on TV and you could hear it through their open windows. They were just trying to get some cool air in. So you could hear the baseball game walking through the neighborhood as you passed multiple different houses.

09:29

I've found some pictures from Cuban magazines of kids playing stickball in the streets, just in the dirt in the streets. You have all of these different memories that constitute the real history of baseball. And the legacy is just an attempt to distill that. So that's a lot of what historical work and archival work is and attempts to do, to recover the full body of that history — although that’s obviously never possible, right? You're always reaching into the unknown to a certain extent.

09:59

But it's also the importance of Topps, the creation of Topps as a sort of chronicler of the national pastime. You have magazines like Baseball Magazine, or in Cuba you have Bohemia Magazine. All of these different ways, newspapers, the New York Times, that are capturing and distilling and conveying and communicating the language of baseball across the nation and across the globe.

10:29

When you look at cultural artifacts, and this is what's so powerful about what happened with Topps and what's ultimately so important about, I'm gonna say this, it's almost like the public institution as a monopoly. There's a certain point where there's a cultural institution or a cultural history that needs to achieve this status of being exempt, which is really powerful. And the historical tension behind this idea is whether this is publicly or privately owned. The Topps company, with all of the economic

10:59

thrust that's behind it, it's entirely individual. For the 50s and 60s, you have some brief interlocutions like 63 Fleer and regional releases and bread releases and things like that. But when you're looking at the full body of what constitutes baseball cards at the most epic high point of American civilization in terms of its global international power and cultural reach,

11:27

as well as the full body of baseball as soon as it comes into the period of integration and post-integration — its solely Topps as the cultural object maker and chronicler in the mythic, spiritual, artistic way of speech. You're looking at something that's so culturally distilled — this specific historical moment and all of the nesting eggs of its simultaneous developments. Again, 1950s, it's Giants, Dodgers, Yankees, right? It's the Battle of New York. It comes back full circle. Interestingly enough, you look at that period and connect it to 1920, 21, 22, 23 —

11:55

which is, again, it's the Battle of New York before mid-century, which is the Giants and the Yankees, the series of consecutive World Series. Then the Yankees ultimately win out. They have Yankee Stadium. They have Babe Ruth’s contract.

12:17

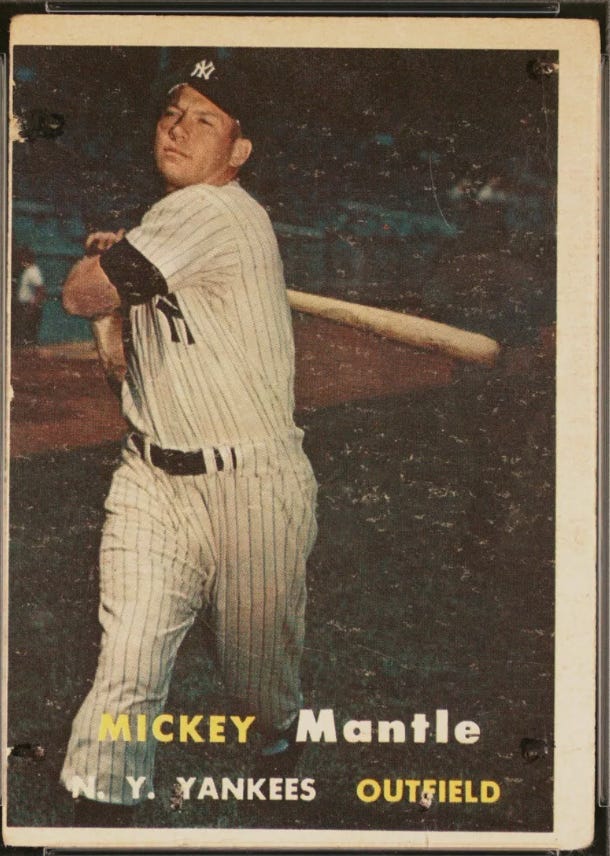

1927 World Series, Murderers Row, you go into the 30s. Babe Ruth's called shot. DiMaggio. The Yankees at this point are a national cultural institution. People wear their hats from all over the world — even if they don’t know what baseball is. It’s that conspicuous. New York rises in the might of the first World War and the industrialization of America and the world and it just doesn’t relent. It happens in the 30s, 40s, but it's just so big in the 50s with Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese and the Dodgers; as well as Willie Mays and the Giants. And then obviously you have Rizzuto, the end of DiMaggio's career. You got Mantle, you got Maris…

12:46

So this is just the core and the reason why I point to New York is because it's the industrial and media cultural super center of the United States. As I said before, was; you could still say is in a lot of ways the world's capital, right? Not only for industry, but for culture. So this is kind of what I'm working

13:11

around here, this idea of monopoly within monopoly within monopoly; even introducing New York and New York baseball, within monopoly. And if you want to take it to that next level, it's New York City, the Yankees, Dodgers, Giants, and then ultimately — the Yankees. And that's all a condensation of political and economic and socio-cultural power. Distilled and drilled down into one Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, or Joe DiMaggio baseball card. And that's so much of what the legacy of the United States has been about, its political and economic power, which obviously, as you can see, has little to no concern with ethics or moral standing and is much more to do with the accumulation

13:41

of power at all costs. So you can see a lot of the cognitive dissonance that happens there when the United States says it's doing something for maybe moral or humanitarian purposes, but it ends up just being for political purposes. What we're talking about here is the cultural institution of baseball as it represents the American mythic cultural subconscious of the entire community or the

14:10

ideological backing of the principle and idea of America itself. It's kind of difficult to talk about, but I mean, the Constitution again is a great example, right? It says one thing and the political reality of America is the accumulation of power at all costs for those who are in positions of aristocratic standing in the country. Not slaves, women. Landowning white men. It says one thing and does another. The parts of the Constitution which everyone knows are its philosophically declarative cultural statements. Does it do what it says its going to do? What it says it is doing? And so,

14:36

you kind of look at the cultural outputs that come from that. Its a founding moment; from foundations emerge branches. Like seed, roots below and leaves above. And I'm not necessarily saying anything is either good or bad here. I'm looking at this from a place of the attempt to understand history. History is not moralistic, or at least real history isn’t, anyways. It’s objective. What comes out of America, I would argue, first and foremost, is baseball. You have Hollywood, of course, as I said before, but when you look at baseball as a cultural institution that embodied the American mythic heroic identity… and it played out in real time, the attempt to create a mythic cultural history. There’s no candle to that in the dream screens of Hollywood. Hollywood is what America dreams, baseball is what America is, lives, moves; be-s.

15:05

What happens in the fifties with Topps; with America emerging out of World War II and the integration of baseball, you have a sort of high point — which emerges through a tension and a contradiction and a paradox — which is, you have the full fledging of the cultural institution of baseball, which had for so long been in development. It's been a century in utero.

15:35

It's building, it's developing, it's creating its identity. Its nursing in the womb of history and time itself, gesticulating. And then all of a sudden you hit the 50s post World War II and everything falls into place. And I don't think it's a mistake that it does when it does, because that's also when American civilization reaches its high point, right? And it reaches its high point through the creation of global war, global conflict,

16:04

where the real stakes of the world are being mapped out for the first and second time in history with World War I and World War II. Again, totally, utterly unprecedented. You could talk about Persia, you could talk about Alexander the Great or Genghis Khan, but never to that extent had the world been in a place of conflict musical chairs, so to speak. So what comes out of that is America as really one of the youngest nations on the scene

16:34

emerges

16:40

with an identity that's arbitrated through war. Civil and World War. And it's interesting to see the parallels between war and baseball, especially in regards to people like Ted Williams or how baseball intersects with the war in terms of how magazines and newspapers convey information to the American public. They both are certainly front page news. I have a great copy of the 1916 World Series news utterly ensconced with global war news on the front page. They're very intertwined. It’s quite telling. They’re very intertwined. Preoccupations of action, movement, force. Political force — this is deeply American. But you see the real soul of America represented primarily in baseball, not through war. And I think

17:09

Hollywood is more of like a commercial industry of dreams. It’s immaterial. It’s selling light and screens, projections which never really come to be. Its a conman’s game. The heart and soul of America is manifest through baseball, through the striving that's there, in the real work of the flesh and sweat and blood in mythic, athletic endeavor — violence without violence — the perfected sport post Colosseum. Whether it's Phil Rizzuto or Jackie Robinson or Lou Gehrig... Babe Ruth, these are American cultural histories. All of them. Babe Ruth is a great example in terms of his childhood. Coming from a foster home, a very troubled child and throughout his life dealt with a lot of very significant psychological,

17:37

physical; mental difficulties and setbacks, but created this larger than life mythic persona through his play on the baseball field. He triumphed, like Mantle, through great existential and personal turmoil through his heroic, mythic ascent on the field of battle without war. It’s like an Achilles, cleansed of blood, replaced with sweat and monk-like, spiritual toil. So you see, it's this sort of cultural theater in the way of the Romans or the Greeks through which you rise mythically or through sport and through athleticism and through engagement with life on real active terms — through engagement with the potentials of what is possible, really, physically, in real time. The embodiment of real physical political force, the perfection of war to the point of which there is no more war. It’s the art of the sport, paramount; perfected, through centuries of development. The Greek god

18:08

Aries or the Roman god Mars. It's that kind of thematic bridge and evolution. Things are playing out through America's development or the ideation and uterine stage of America's development through that active principle. Through active physical force and how to spiritually evolve through real engagement with the potentials of the flesh, movement, and the will. So to go back to the monopolies — there's almost this transcendental alignment that occurs there in the 50s:

18:37

with Topps, with America emerging from global conflict as international victor; the monopoly of Major League Baseball and its full integration. And this additional mid-century layer of New York City baseball identity: Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle. There's this sort of mythic core

19:06

that reaches its utter height at that period of time. Layers within layers within layers, like a fractal. And it's just fascinating to see how it manifests through, I think the lens is really, again — the baseball card. And that's why I keep coming back to that topic, because it's the way in which the myth is represented; its condensed and coalesced through multiple different things. The T206, which — again — is the first modern baseball card, or the big modern baseball card that emerges

19:36

at that industrial pivot point which we discussed right before World War I. You have that unfolding of the history of the baseball card, the T206 to Topps. You can see a lot of those early caramel and tobacco releases in what Topps does, especially in terms of the flat colors and the cutout players. That's developing as a through-line, a timeline. Major League Baseball is developing —

20:00

right from the late 1800s through the segregation period through the Cuban leagues and the Negro Leagues to the ultimate integration in 1947. You have that which culminates there. And then you have the larger history of American civilization itself, which is developing from the Constitution to the period of internal conflict through slavery and segregation in the 1800s through the period of global war turmoil —

20:30

in which people of all creeds and colors engaged in this war. And then ultimately the integration in the 50s and then this period of intense civil fomenting in the civil rights movement, which Jackie Robinson was a big part of, as well as the...

20:53

massive cultural, social changes that happened in the 60s — connected especially to the Vietnam War, Kennedy, Cuba. Again, big theme, Cuba comes in. So you can see the network that I'm trying to draw here. There's this massive intersection between baseball history, American history, and world history. It's a picture that could probably never truly be summed up in terms of its magnitude and the difference and the contrast that occur within it.

21:22

But you can see how important it is that Cuba goes through its independence movement at the end of the 1800s, really intersecting a lot with what the US Civil War movement is, does, and is doing in the US internal self narrative. The Cuba independence movement is a national liberation movement as well as an abolition of slavery movement. And then the Spanish American War right at that 1900 period. Leap forward into the 50s and 60s, Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy, Castro.

21:51

These are themes that are emerging, receding and emerging in relationship to and through baseball. When you look at American history through the lens of baseball, you're actually able to see America's attempts to come into being. You can see the myth manifesting. Not the story the nation wants to tell itself, as in cinema and Hollywood — no… the story of the nation itself. Its real, live, living, active attempts to self-realize and self-actualize. It's the medium through which America is actualizing, the same way that maybe an artist has a paintbrush or a musician has a guitar.

22:19

For America, the medium of actualization is baseball. It's a very, very nuanced and subtle thing. And so when you look through the lens of a historian or a philosopher or archivist at baseball, you're looking at how is baseball representing itself, not presenting itself in terms of the action on the field and this and that, but rather how is it representing itself in terms of its cultural artifacts? And so there's a couple of different ways to look at that. You have the photographs, which are

22:48

— it's not baseball representing itself, it's the news capturing baseball. You have newsprint, similar thing, television. These are all things that first that you could kind of say, you know, this is baseball representing itself. But you have to look for a mythic distillation of the image. And that's usually iconographic. Its the crossroads between the dreaming and waking state. It’s hyperbolic, religious, spiritual, liminal. It's not literal, it's not documentary. So when you look for that iconographic imagery, what you find is the baseball cards.

23:17

So the history of the baseball card is the history of the image representation of the American self as it is in the period of its most intense formative development, which is 1900 to 1950 or 1960 — because now we're attempting to distill national liberation; abolition of slavery

23:45

with a rapidly emerging industrial global environment and create and cultivate a collective identity that is not segregationist, it's not isolationist, it's involved in a global community. But its still ‘American’. Its still defined. Who is us? Who are we? What is ‘America’? Identity is separative. But the world is rapidly breaking and blurring all boundaries and borders. Religious, cultural, racial, technological, national. So you can see how for a young nation that's immediately jarring. There's very little time that America exists in a regional period of privacy, right, as opposed to Italy or China or Greece.

24:13

These are areas, they've existed for hundreds and thousands of years. They had regional relationships, sometimes more semi-global, like with the Silk Road. There's a lot of different areas that are coming into relationship in the Silk Road. In terms of the world historical intersection of the United States' developmental phase; as that relates to the awakening of the world to a truly global reality — its seismic. When we look at the 50s — I'm just going to reiterate it one last time —

24:42

you have the height of American political power in terms of the international revolution of the end of World War I and World War II, where America emerges clearly the undisputed global victor of that conflict, even within the victorious faction of the Allies.

25:04

You have the birth of the absolutely condensed, consolidated, typified modern baseball card with Topps. The entire history of baseball card has been distilled and presented through one dominant, mass institution, which is also a private company — which is Topps. This is the summit. The emergence. And the emergence of modern baseball:

25:26

baseball is allowed to be a monopoly as of the 1920s, but it becomes America's national cultural institution in an entirely integrated and holistic way when integration occurs. 47, Jackie Robinson, technically the official integration of baseball and then into the 50s. Larry Doby, Minoso. So that's the episode there. I hope you enjoyed this. It's a big picture perspective and there's a lot of moving parts,

25:54

but I think you can see the picture that I'm painting with a broad brush here. I hope you enjoyed. I'll see you on the next one.