The Fulfilled Promise of The American Revolution: Democratic Ownership & The T3 Turkey Red Lithographs

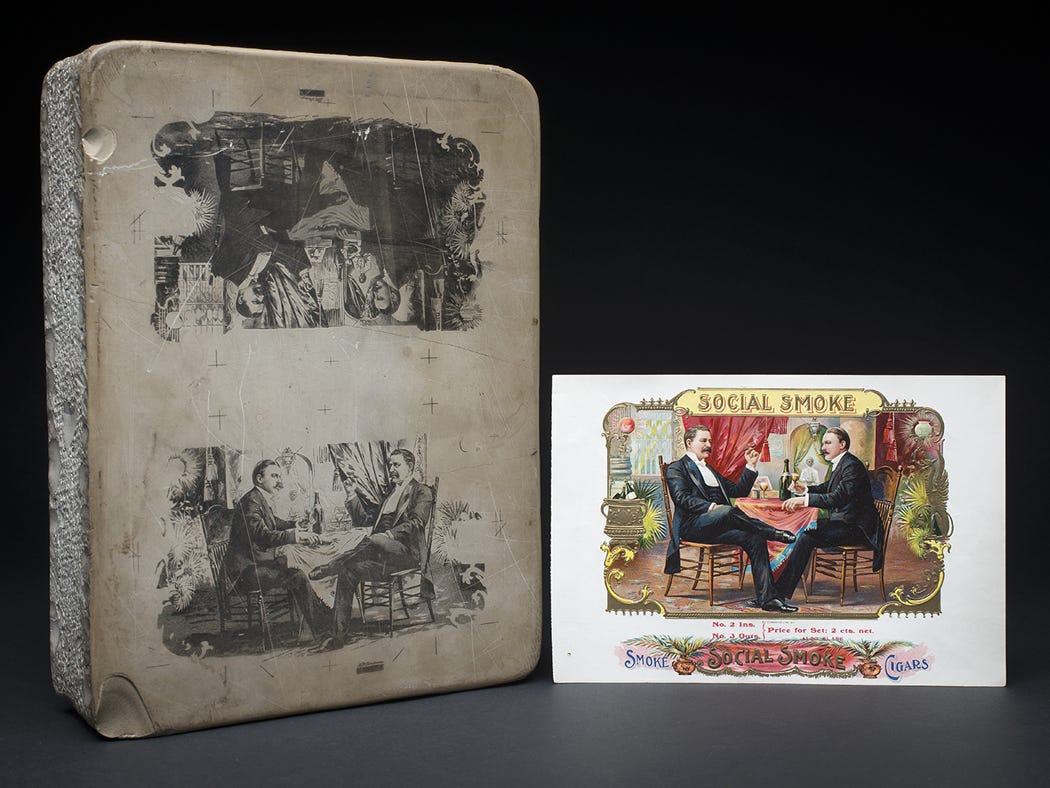

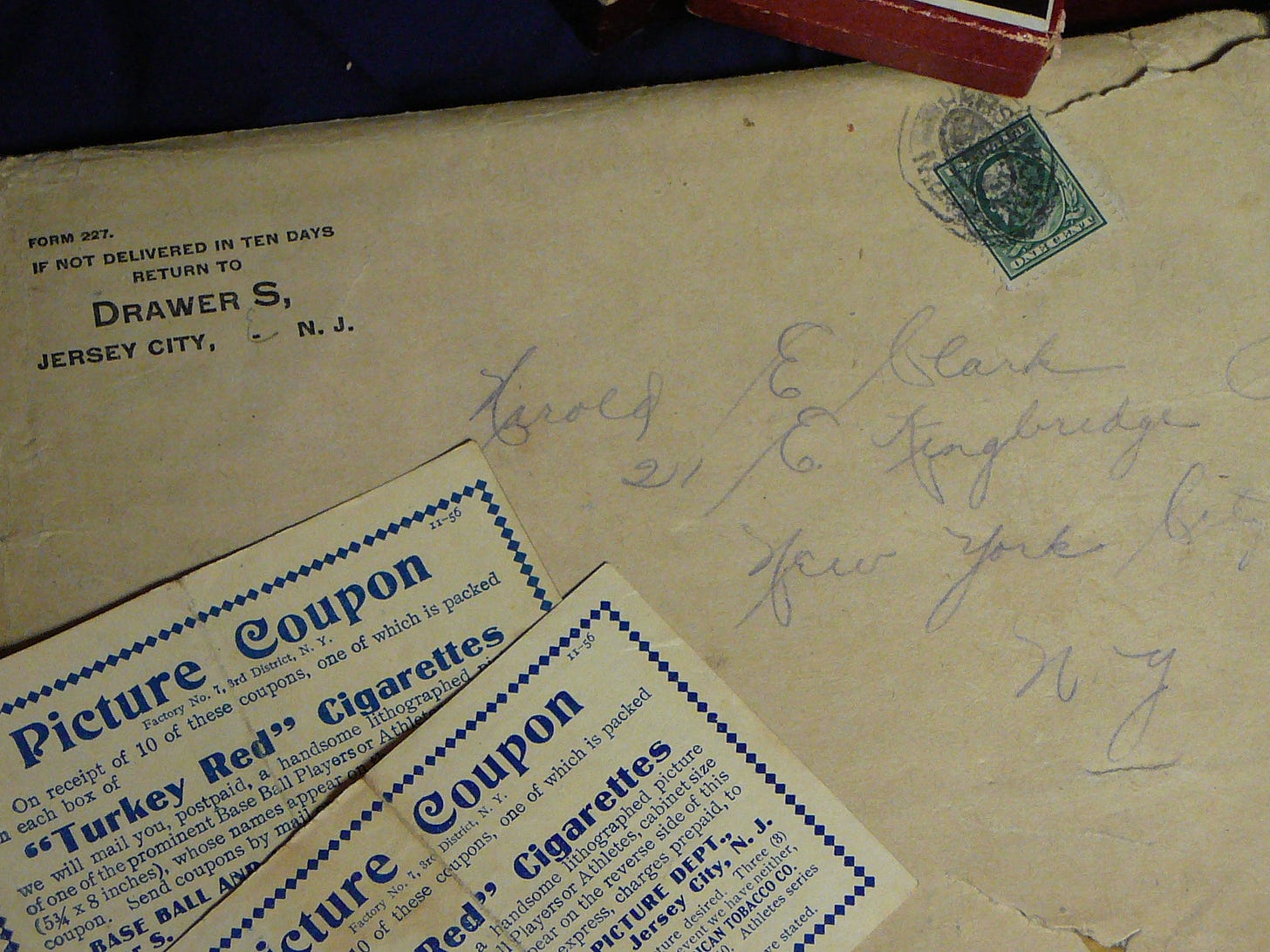

Above is a remarkable example of the craftsmanship and everyday use of the 1911 T3 Turkey Red chromolithograph. The first image, or image 1, features Hall of Fame pitcher Vic Willis (#40 on the checklist) completing his delivery.

Willis was celebrated for his durability and consistency, routinely completing games and recording eight seasons with 20 or more victories. As the ace of the staff, Willis, alongside baseball legend Honus Wagner, helped lead the 1909 Pittsburgh Pirates to a World Series victory over Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers. By this time, the World Series had become a national media event, covered extensively across the United States.

The backside of the T3 lithographs, or image 2, often featured offers like the one above, showing how these fine art prints were made accessible to wide swathes of people across class lines through the redemption of Turkey Red cigarette coupons. This revolutionary system allowed for the mass distribution of art, blending high art with everyday consumer culture and enabling people from all walks of life to own and display these images in their homes. This broke down traditional barriers between high art and the public.

Beyond their exquisite multi-layered stone plate coloring, chromolithographs—including the 1911 T3s—were often meticulously hand-touched by artisans and draftsmen. This additional handwork amplified the visual impact and resonance of the images, adding depth and vibrancy to these already stunning prints.

The Lost American Art Revolution

Long before Abstract Expressionism, America had already staged an artistic revolution. This revolution did not take shape within museums, galleries, or royal courts—nor was it merely a matter of style, painterly craft, or individual genius. Instead, it arose through mass production, cigarette coupons, and working-class hands.

The 1911 T3 Turkey Red lithographs were not just, or even primarily, baseball collectibles. They were fine art masterpieces hiding in plain sight.

The narrative of American art has traditionally emphasized fine art movements that parallel or respond to European traditions, with Abstract Expressionism positioned as America’s first major contribution to international art discourse toward mid-century.

Yet this perspective overlooks a radical visual culture—one that emerged through commercial printing technologies in early 20th-century America, reshaping the very meaning of fine art.

The T3 Turkey Red: Context and Production

The T3 Turkey Red series consisted of large-format lithographs (5¾" × 8") printed on thick cardboard stock, featuring baseball players and boxers. The large format and thick stock choices were deliberate ones to make the T3s feel substantial—more like framed portraits and large cabinets than trading cards.

These premium items were available through coupon redemption programs associated with the Turkey Red cigarette brand via American Tobacco; commissioned by The American Tobacco company to The American Lithographic Company. Over 100 different subjects were produced in the series, with an estimated 8,000+ examples surviving today.

These lithographs were crafted using multi-stone chromolithography, a labor-intensive process requiring up to 20 separate stones for color layering. This technique allowed for extraordinary tonal depth and dimension, rendering each lithograph nearly indistinguishable from a hand-painted artwork—far surpassing the quality of standard printed images of the time.

The American Lithographic Company’s team of artists and artisans were some of the most well trained in the world at the time, with deep roots in European printing traditions—deeply literate in the most advanced and efficient techniques used for high-end posters, trade cards, labels, and art prints in varieties of quantities; produced at speed or with pace.

Not only were the artisans at American Lithographic Company advanced and innovative artists in their own right—they were also powerfully skilled, highly modern industrialists—capable of churning out prints and materials quickly while maintaining the utmost fine grade caliber of product.

Lithography—or stone printing—was invented in 1796 by Bavarian author Aloys Senefelder. Lithography is a process where an image is first drawn on a large stone slab with an oil based pencil. The stone is moistened with water, then, the areas drawn with the pencil repel the water— as oil and water do not mix. When the surface is coated with an oil based ink, the ink only adheres to the area where the image is drawn—this area translates into the printed design.

In 1837, French printer Godfrey Engelmann patented the process of chromolithography—using the lithographic process to create full color images by separating them into a series of different colored printing plates. Later in 1846, American inventor Richard M. Hoe perfected the rotary lithographic press that could print six times as fast as the original flat bed lithographic press.

Lithography and chromolithography freed designers and illustrators from the linear confines inherent in the format of the type-bed used in the standard movable type printing process. It presented the opportunity to create letter-forms that curved, slanted and bended in countless directions. It also presented limitless freedom of form. The designer was no longer bound to the process of carving letter-forms from wood or metal; the characters could now be drawn by hand. Chromolithography is also one of the first practical methods of combing multiple colors together to achieve the full color image.

The process of Chromolithography defined the visual aesthetic of graphic works from the Victorian era. Colorful packaging lined the shelves of shops, chromolithographic prints were commonly found in people’s homes, and the colorful illustrated style associated with the process was a perfect fit for the format of children’s books which became popular during the Victorian period.

— Gabriel Stromberg, The Catalyst of Industry (2022)

The Art Historical Revolution of the T3 Turkey Red Lithographs

In the early 20th century, new printing technologies transformed visual culture, pushing high art into unexpected spaces. The T3 Turkey Red lithographs emerged at a moment when the boundaries between commercial and fine art were becoming increasingly fluid.

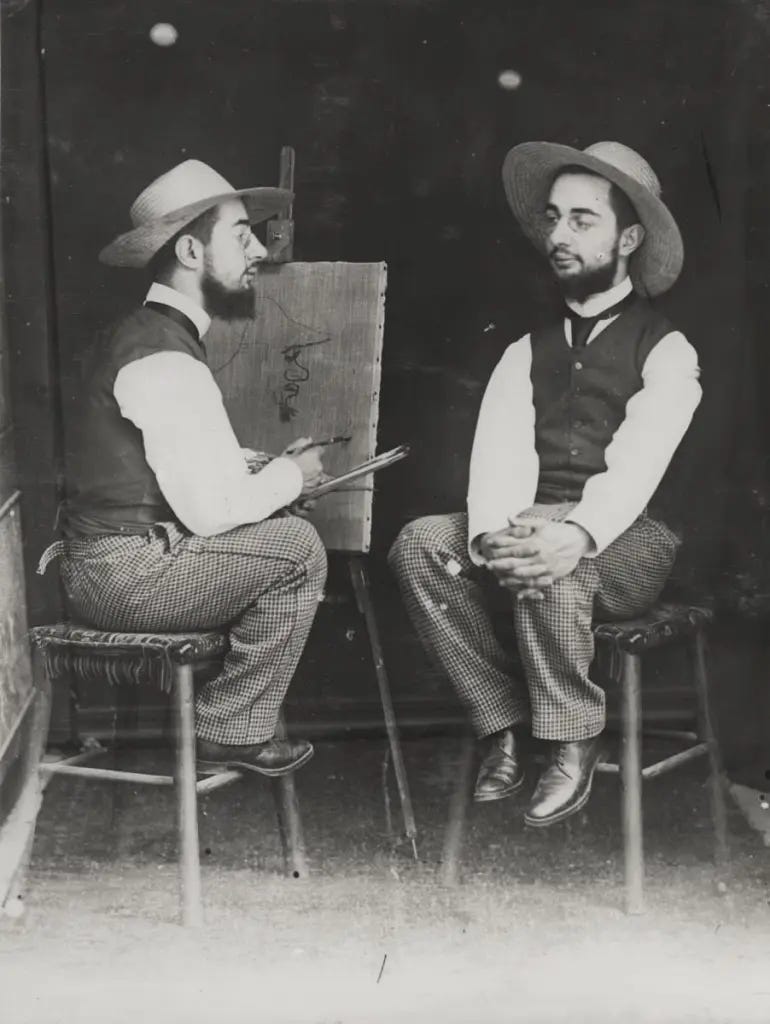

Artistic Lineage: The chromolithographic techniques employed in the T3 series drew from the same technological innovations that produced fine art prints and Art Nouveau posters. Artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha had already demonstrated lithography’s artistic potential in Europe, displaying prints and posters in shops and public spaces.

Craftsmanship: The multi-stone lithographic process required skilled artisans with advanced artistic training. The quality of draftsmanship and color work in the T3 series reflects this expertise, with each print painstakingly drawn and colored—capturing American pastoral landscapes and early industrial cityscapes.

Aesthetic Qualities: The T3 lithographs exhibit carefully composed figures, dynamic poses, and sophisticated color relationships—transcending purely commercial considerations. These qualities align them more closely with the fine art of their time, bearing resemblance to the figurations and environments of Otto Dix, Toulouse-Lautrec, and other European painters.

The T3 Turkey Reds were not baseball cards in the traditional sense—they were fine art lithographs masquerading as commercial ephemera. Meticulously crafted using the same techniques that defined high art, T3s were the first true fine art objects to be directly owned by the working class—disrupting traditional gallery, market, and institutional models.

Unlike earlier mass-printed images, which were either publicly displayed (posters) or required direct purchase—such as the Currier & Ives prints of the 1800s (which were of notably lesser quality with basic color layering on thin paper stock), or even the Japanese Ukiyo-e prints of the 17th-19th centuries (which, though artisanal, remained bound to commercial transactions and were stratified in quality based on class access)—the T3 lithographs were free high-art chromolithographs, printed on substantial, heavy stock with top-quality inks. Available across social lines at an exacting high-art standard via cheap cigarette coupons, they were not merely collected but lived with, touched, displayed, and personally owned.

This was not just an innovation—it was a revolution in how fine art was created, distributed, and owned. And it was made possible, in large part, by the unity of craft and modern industrialization - a radical advancement without true historical precedent.

Woodblock print titled Toyosumi from Choji-ya (House of the Clove) by the artist Harunobu, created in 1770. Ukiyo-e prints were produced on thin, high-quality paper, often made from mulberry or kozo (mulberry tree bark). This paper was ideal for printing as it could easily be rolled or folded for distribution and transportation.

Ukiyo-e, particularly of this quality, were more affordable than original paintings - making them accessible to a broader audience, including lower social classes. This accessibility allowed Ukiyo-e to become deeply embedded in the daily lives of ordinary people.

This democratization of fine art is a defining characteristic shared by both Ukiyo-e and the T3 Turkey Red lithographs. Renowned artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige not only revolutionized the art world in Japan but also deeply influenced global art movements with their innovative styles and powerful imagery.

Why Did American Tobacco and The American Lithographic Company Create the T3?

Baseball, rapidly emerging as America’s national pastime, needed formal visual representation. T3s, developed during the boom and boon of press photography as a way to get sporting heroes such as Nap Lajoie and Honus Wagner in front of hundreds of thousands of eager fans who lived across the country, were an early form of myth-making—elevating players to near-mythological status.

American Tobacco was well aware of this emergent phenomenon of America’s pastime while establishing their marketing and promotional campaign—for which the Turkey Red large format lithographs were the prize. Already the biggest tobacco brand in the country in 1900, just two decades after their founding, ATC was on the verge of a massive anti-trust suit. It simply could not be denied. Founder J.B. Duke (whose family name is upon Duke University, due to a massive endowment) and American Tobacco produced over 80% of the tobacco on the American market; were in violation of the restraint of trade and monopoly laws established by The Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890.

Not at all coincidental to the industrial art revolution Duke was about to undertake with ATC was the method by which he obtained his extreme market dominance: being the first man in the industry to seriously invest in the cigarette rolling machine - invented by James Bonsack in 1880. This fast and cheap production method skyrocketed his profits, while minimizing his overhead and labor costs. With company equity rapidly approaching half a billion dollars; the Supreme Court knocking on his door to dissolve American Tobacco, Duke was engaged in an intense and climactic battle for complete and utter market dominance.

Enter the T3 lithograph. Duke, who was already engaged in producing the now world famous and contemporaneously popular T206 cards (which were inserted directly into tobaccco packs in 1909-1911 and include the most famous baseball card in history, the T206 Honus Wagner), decided to up the ante.

Packages of Turkey Red (the flagship brand under ATC for the T3 promotion), Fez, and Old Mill would contain coupons—10 Turkey Reds, or 25 Fez/Old Mills could be redeemed for a T3 lithograph, which would subsequently be sent in the mail. Duke and American Tobacco wanted to create something that people would want to keep, frame, and display—ensuring long-term brand exposure for the company; full market dominance for years to come. In order to do so, the Turkey Red T3 chromolithographs would have to reach new, unprecedented heights as a promotional item. The T3s would have to be produced with the most exacting, fine art standards—to create a prize people would never forget; cement the legacy of ATC in the minds and hearts of the American populace at large ad infinitum.

We cannot be sure today if Duke, American Tobacco, and The American Lithographic Company understood in full sum what the Turkey Red lithographs were and would become, nor what their system and method would truly mean in light of the grand scale of history and culture. But we can uncover the true meaning and true power of this perfect storm of events—events which rendered one of, if not the greatest, revolutionary processes and works of mass, collaborative, democratic modern art.

America’s First Industrial Fine Art Movement—Preceding Europe’s Modernist Avant-Garde

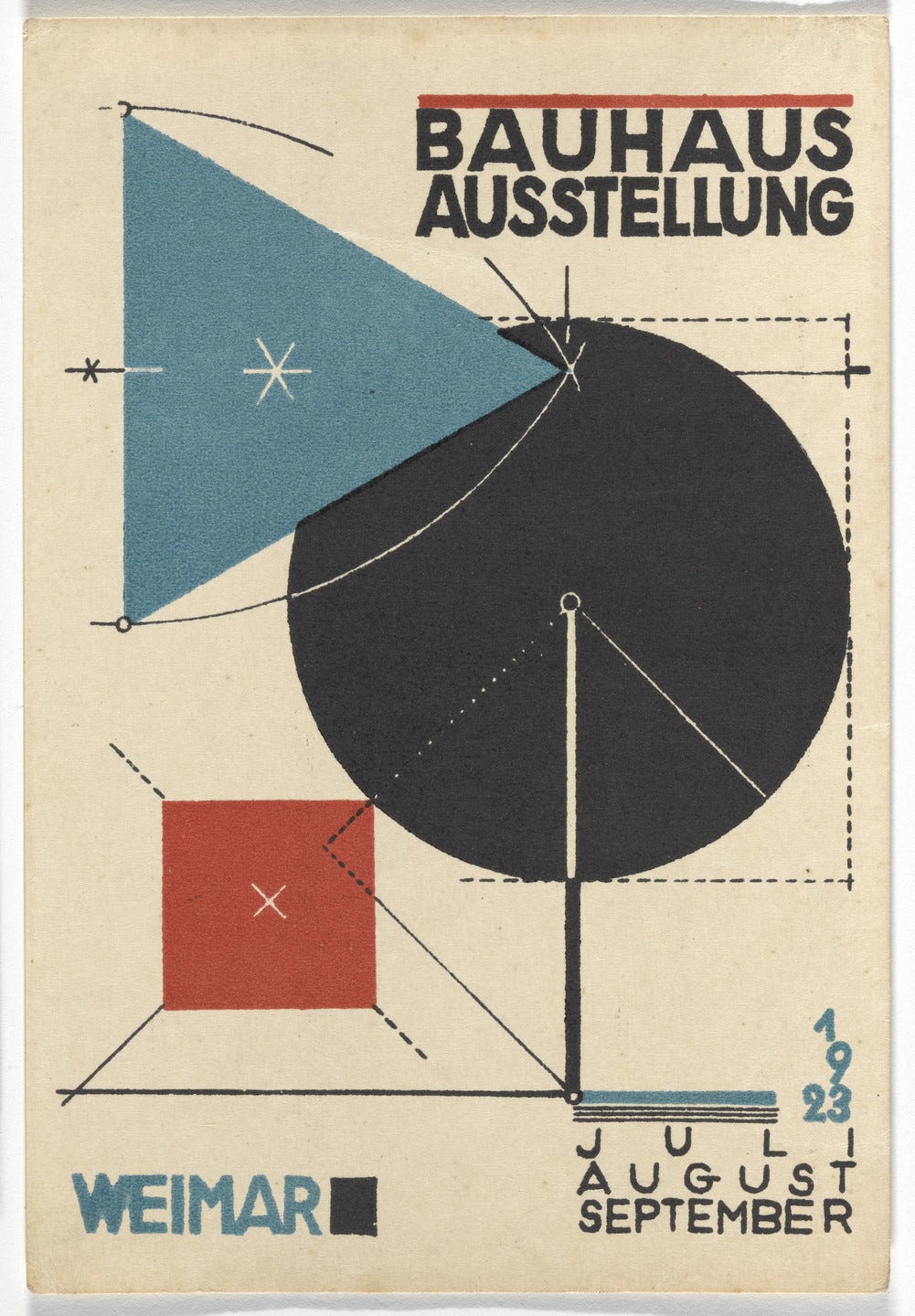

While the European avant-garde has long been credited with bridging fine art and industrial production, the T3 Turkey Red lithographs of 1910-1911 preceded and surpassed every major European movement in both execution and reach. Constructivism (1915-1925) sought to integrate art into industrial design, but its work remained confined to state-sponsored projects and elite circles—never achieving true mass ownership.

Bauhaus (1919-1933) theorized the unity of fine art and industrial production, yet its influence was restricted to academic design exercises rather than mass-distributed, lived-with artwork. Dada (1916+) engaged with mechanical reproduction, but only as an esoteric critique of mass culture, never an integration with it. Even Pop Art (1950s-60s), often seen as the first true embrace of commercialized fine art, arrived decades too late. The T3 lithographs had already fused high art, industrial production, and mass ownership with greater sophistication and deeper cultural penetration.

The T3 Turkey Reds were not an avant-garde experiment or theory—they were a radical cultural transformation in action, fully realized in ownership, access, and distribution. Unlike their European counterparts, they placed museum-quality craftsmanship directly into the hands of thousands, cutting across class lines by way of promotional material in a product meant to reach the widest possible net.

In this sense, American industrial fine art did not merely precede the European avant-garde—it eclipsed it entirely, propelled by the sheer momentum of an industrial superpower surging toward dominance. The T3s emerged at the precise inflection point of America’s rapid ascent, embedded within one of its most powerful mass-market products—a perfect synthesis of art, industry, and economic force.

These chromolithographs surpassed European efforts in both artistic rigor and social revolution, employing multi-stone printing techniques that rivaled the craftsmanship of oil painting, while simultaneously achieving mass fine art ownership on a scale no European movement ever accomplished. The T3s did not require a manifesto, an art school, or government control of content, themes, or placement—they simply placed high art directly into the hands of ordinary people. This was not just mass production—it was mass democratization of fine art before the term even existed.

El Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) is often heralded as a pioneering example of mass-produced fine art in Europe and Russia. Created as Bolshevik propaganda, it embodied Constructivism’s goal of merging industrial production with fine art—using bold geometric abstraction and high-contrast lithography to communicate revolutionary ideals. Like the T3 Turkey Red lithographs, it demonstrated that mechanical reproduction could function as an artistic medium rather than merely a tool for advertising or documentation.

Yet the critical difference lies in access, ownership, and execution. Lissitzky’s work was widely circulated as a state-commissioned ideological tool, but it was never personally owned, lived with, or integrated into private spaces on a mass scale. By contrast, the T3 lithographs were voluntarily acquired through consumer engagement, making them truly democratized in both distribution and ownership. Additionally, while Constructivism prioritized simplified geometric forms for maximum reproducibility, the T3 lithographs maintained museum-quality craftsmanship—utilizing multi-stone lithography, hand-finished detailing, and a rich color depth that rivaled traditional oil paintings.

Constructivism marked Europe’s first significant attempt at industrial fine art, but it emerged nearly a decade later—and even then, it remained largely tied to institutional and ideological frameworks. The full-scale democratization of mass-produced fine art had already taken place in America with the T3 lithographs, which seamlessly fused high art, industrial production, and widespread accessibility in a way no European movement ever fully realized.

Lissitzky’s Red Wedge, for all its innovation, was distributed but never possessed. It was an instrument, a tool—never something people could claim, display, or make their own. Seen but never held, circulated but never lived with, it remained a statement, a movement, a call to action—but never a tangible, personal artifact that could be truly owned, touched, and called home by the people.

The T3 lithographs, by contrast, were art by and for the people—objects that entered homes, absorbed light, collected dust, and became part of daily life. Crafted by anonymous artists, their work remained untouched by the status-driven inflation of the fine art world or the detached theorizing of early modernist avant-garde circles—circles that critiqued reality from afar, claimed to reshape it, yet remained walled off from the actual lives, desires, and struggles of the people. Not theoretical, but tangible—they were owned, handled, pinned to walls, engaged with in ways both deeply personal and inherently political. No European avant-garde movement ever achieved such direct access or immediate cultural authorship.

The T3s were a fully realized vision of industrial fine art and radical democratic politics—executed before Europe or the Russian revolutionary arts could even conceive of it. T3s perfected a form of total democratic politics before the rest of the world’s most revolutionary vanguards could jettison themselves from the purely theoretical, ideological, speculative stage of the liberation of fine art.

Breaking the Barrier: How the T3 Lithographs Destroyed the Divide Between Fine Art and Mass Culture

The T3 marks a fundamental and revolutionary break from the European model, where fine art remained confined to galleries, aristocratic collections, courts, and intellectual circles. T3 lithographs shattered this exclusivity—bypassing the traditional gatekeepers who dictated production, themes, and access to fine art.

Unlike traditional fine art, the T3 crossed class lines—distributed via cigarette coupons and depicting sports scenes that resonated universally. Hand-reproduced at an industrial scale—not for gallery elites but for everyday people—the T3 series redefined ownership of high art and dismantled the traditional hierarchies of Western art history.

This was a revolutionary paradox—the merging of high art and mass culture in a way that predated Warhol’s Pop Art by over half a century. Unlike later movements that merely reflected on mass production, the T3 lithographs embodied this fusion at its peak—seamlessly integrating fine art with industrial reproduction while preserving the meticulous craftsmanship and human integrity of the handmade.

The T3 Turkey Reds—high art distributed through mass consumption, not to the elite but to factory workers, shopkeepers, and immigrants—depicted a game that had captured the hearts, minds, and imaginations of Americans across all social strata. This was fine art that was not seen from afar (if at all)—but actively incorporated into the daily lives and living spaces of civilization at large.

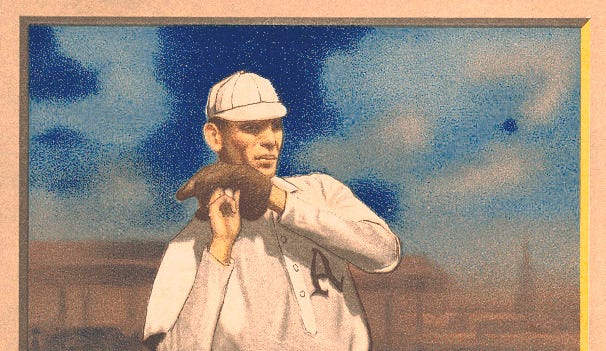

The softened yet stark rendering of Bender’s expression, almost spectral haze of the backdrop, and the precise yet dreamlike handling of color elevate this work of industrial modernism beyond mere documentation into something mythic, unsettling, and deeply human.

Democratization Through Commercial Channels

The distribution method of the T3 Turkey Reds offers an unparalleled case study in the democratization of fine art; it is at the center and is the true source of their art historical and cultural revolution. Unlike museum pieces or gallery prints, these lithographs were accessible through everyday consumption:

The Coupon System: Consumers could redeem coupons included with cigarette packages for these premium lithographs, bypassing traditional art market structures. This system of coupon-based exchange in everyday commerce reveals how industrial-era American markets pioneered a radical new model for democratizing fine art. This method would later become increasingly common in baseball cards; other tokens, stickers, and incentivized prizes for purchasing and using particular brands and stores.

Working-Class Access: This system placed high-quality color lithographs in the hands of consumers across various socioeconomic backgrounds. Unlike traditional gallery-bound artwork, these lithographs were accessible through the daily act of smoking—one of the most universal working-class habits in early 20th-century America. Turkey Red cigarettes were cheap, commonly purchased by factory workers, immigrants, and store clerks alike. Whether a person was a laborer in Pittsburgh, a shopkeeper in St. Louis, or a newly arrived immigrant in New York, access to a Turkey Red lithograph was simply a matter of choosing a brand at the counter. It was fine art available at street level—by design.

Personal Engagement: Physical evidence on surviving examples, such as pinholes and wear patterns, suggests these items were displayed and integrated into domestic spaces rather than treated as precious collectibles. This, accordingly, turned these domestic spaces into private galleries for people across class and social status lines.

This model of distribution was a radical transformation—it brought fine art into the realm of the everyday, much in the way that artisanal silver gelatin press photography was reshaping the documentation of history through the reproduction of high art images in the daily newspaper for large swathes of the public.

This emergent modernity had two distinct forms: press photography, which remained archived in newsroom vaults, and T3 lithographs, which were mass-produced for personal ownership.

Despite its radical nature, this fine art revolution remains absent from art history. Unlike museum-held paintings or gallery prints, T3 lithographs were owned, lived with, and displayed in working-class homes—rendering them invisible to the institutions that define 'fine art’. The museum model, built on scarcity, control, and curation, had no way to assimilate a form of high art that was both mass-distributed and commercially redeemed. As American art criticism shifted toward Abstract Expressionism and the postwar avant-garde, the T3 Turkey Red lithographs—one of the greatest experiments in the democratic ownership of fine art—were quietly forgotten.

The Vic Willis Example: Material Evidence of Engagement

Individual artifacts can provide valuable evidence of how these lithographs functioned in their original context. One specific T3 Turkey Red featuring pitcher Vic Willis (checklist #40, SGC serial number 1278479-017) bears remarkable physical marks of its history:

Display Evidence: A pinhole at the top center indicates it was likely hung on a wall, suggesting its decorative function in a sparse, direct, and raw form. It was not framed, nor was it preserved with delicacy - it was rather pierced and displayed.

Usage Patterns: Cigarette burn marks above the nameplate suggest casual handling, completing a full provenance loop from acquisition to lived experience. One can imagine the ember of a Turkey Red cigarette leaving its mark on the very artwork obtained through its purchase.

Preservation Despite Use: Including these marks of handling, the lithograph retains great depths of its original color vibrancy; the entirety of its object body. The contrast of the preservation of the rest of the artifact even in light of the stark burn marks and pinhole piercing is stunning.

These physical characteristics remind us that these objects existed in lived spaces, not merely as collectibles or ephemera; accordingly, were displayed like works of art in the most practical ways. Unlike untouched examples stored away, this Willis T3 was actively engaged with in the process of daily life, making it one of the rarest and most valuable forms of fine art—a piece that was lived with rather than merely preserved: a democratic work of art.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was revolutionary in every sense of the word. His depictions of the Parisian underworld, his innovative use of cardboard and lithographic techniques to produce mass media, and his fearless approach to subjects from all walks of life solidified his legacy as a paradigm-shifting figure in art history.

Lautrec’s portrayals of prostitutes and the energetic world of the Moulin Rouge—along with his bold use of vibrant, textured color—set him apart, aligning him with his fellow Frenchman Vincent van Gogh, whom Lautrec knew personally. He exhibited together with Vincent in Paris; Theo, Vincent’s brother, purchased Lautrec’s Poudre de Riz (1887) for the Goupil & Cie gallery.

A loyal friend and champion of van Gogh, Lautrec once challenged an artist to a duel who dared to criticize Vincent. A visionary in technique and character, Lautrec’s social and aesthetic revolutions charted the course for a radically new modernity.

Parallel Developments: Photography and Mass Visual Culture

The T3 Turkey Reds emerged during a transformative period in American visual culture that included several parallel developments:

Press Photography: The rise of photojournalism, coupled with rapid advancements in image transfer from original prints and negatives to newsprint—as well as improvements in shutter speed—transformed how Americans consumed visual information. Press photography was not merely captured—it was sculpted. Just as lithographers layered ink for tonal depth, newsroom artists meticulously retouched photographs by hand, enhancing highlights, shadows, and textures. This process, largely forgotten, reveals that both T3 lithographs and press photographs were part of the same hidden fine art revolution.

Advertising Art: Commercial illustration was reaching new heights of sophistication and cultural influence - finding more and more public and personal space for creative assertion.

Cinema: Moving pictures were establishing themselves as a dominant form of visual entertainment. This desire for cinematic and archetypal depictions for daily life and which elevated daily life to the realm of the mythic and archetypal touched and trailed all of the concurrent visual forms of the age as a part of the mass democratization of visual art and the image through industrial revolution.

The T3 lithographs should be understood as part of this broader ecosystem of visual media that was reshaping American cultural consumption. Their significance lies not in isolation but in their participation in this larger transformation.

Depicted above is former New York Yankee, Ping Bodie—an emerging power hitter during the tail end of baseball's ‘deadball era’—captured mid-swing in a 1919 silver gelatin press photograph, recovered from a news archive.

As shown in images 2 and 3, press photographs were meticulously altered by newsroom artists, much like lithographers refining color gradations with multi-stone prints. Additionally, it is essential to note the exceptional quality of the original silver gelatin print itself: the depth of hue, the clarity of motion captured, and the photograph's development in the darkroom—crafted through the master photographer’s skilled relationship with the negative. This photographer, like many of the profoundly skilled newsroom craftsmen of this era, remains unknown.

The hands, bat, legs, and uniform have all been rigorously retouched by hand, demonstrating that both mediums were shaped by a shared industrial, hand-crafted fine art ethos—from the initial draftsmanship and photo development to the manual alterations.

The Final Revelation: America’s Artistic Revolution

Art history has long treated European traditions as primary and American innovation as secondary until post-WWII. But by 1909-1915, American art had already surpassed Europe—not in oil painting or sculpture, but in mass visual economy, culture, and production.

The Willis T3 becomes the most direct, definitive, and utterly personal proof of this shift:

It was handmade yet mass-distributed—a stone lithograph created with the precision of gallery art but given away freely. This form of democratic ownership as a revolution in a fine art historical sense is not present anywhere else in the media forms of the time.

It was meant to be engaged with, not just looked at—it wasn’t preserved in a museum but lived with in daily life. These pieces straddled the display quality of a gallery art object with the lived reality and experience of the individual.

It is the singular artifact that captures the totality of this revolution—a fine art object that lived within, flourished within, and embodied industrial culture - down to its rapidly shifting and accelerating vision of democratic participation in modes of seeing, knowing, and owning high art.

This is why the Willis T3 isn’t just an extraordinary object—it is one of the most important surviving artifacts of modern art history. It stands at the precise threshold of a profound technological revolution in human history. Rather than succumbing to the rigid portraiture-for-kingship paradigm of the past or dissolving into the mass-produced commercialism of the future, it achieved something rare: a primordial unity that redefined what fine art is and can do—how it is expressed, owned, seen, and understood.

It is the realization of a lost revolution—the singular moment when fine art was truly democratized before being reclaimed by scarcity, exclusivity, and commodification.

And it exists, paradoxically, because it was lived with, not because it was preserved.

The Willis T3 is not merely a relic—it is the missing key to America’s lost artistic revolution. It is proof that fine art was once democratized, owned, and lived with by the many—before being reabsorbed into systems of scarcity and exclusivity. The T3 Turkey Red lithographs are not a forgotten footnote in American art history. Rather, they are evidence of a seismic shift that redefined what fine art is, who it belongs to, and how it functions in civilization. This is not just a revelation—it is a reckoning. A reckoning that demands the very foundations of 20th century art history be rewritten.

For over a century, fine art has been defined by what institutions, collectors, and critics deem worthy of preservation. But the T3 Turkey Red lithographs exist outside this system—they were never meant for galleries, nor were they objects of wealth-hoarding. They belonged to everyone. If modern art history refuses to acknowledge this revolution, it is not merely an oversight—it is an erasure of the most radical democratization of fine art in American history. The rewriting of 20th-century art history is not a choice. It is a necessity.

Bauhaus theorized mass-produced fine art—T3 lithographs actually executed it over a decade earlier.

Reckoning with Rewriting History

At its core, the fusion of high art, process-intensive press photography, and the radical democratic fine art of the T3 lithographs reveals a hidden and unrecognized industrial fine arts movement in early 20th-century America—one that merged technical mastery with mass cultural engagement on an unprecedented scale.

This movement prized and prioritized intensive craft in drawing, shooting, and developing top of the line artistic prints (both in photo and litho) - prints which are most abundantly and clearly expressed through America’s most essential cultural art of movement at the time: the athletics and sport of baseball.

This movement remains unrecognized—not just for the stunning artistry of its prints (crafted by still-unknown artisans in industrial workshops) but for its radical democratization of fine art. It shattered the Western model of high art as an exclusive commodity. No artifact embodies this forgotten revolution more powerfully than the T3.

Otto Dix (1891–1969), a leading figure of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, embraced radical realism and sharp physiognomic exaggeration to expose the raw truths of his subjects. His Self-Portrait with Easel (1926), with its precise yet distorted features, mirrors the T3 lithographs’ own heightened, almost surreal caricatural depictions of baseball players—employing industrial fine art techniques to elevate their subjects beyond naturalism.

By the time he painted this work, Dix had fully transitioned from the gestural energy of Expressionism into the cold precision and satirical realism that defined New Objectivity. His subjects—often grotesquely detailed and psychologically unfiltered—were shaped by his service in World War I, where he fought at Somme and Verdun. The mechanized slaughter of war and its serialized destruction of human life forever marked his artistic vision. Baseball’s own tangled industrialization—cut with gangsterism, gambling, and the struggle for political power over the sport—uncannily mirrors the seismic shifts in Dix’s postwar art.

Both Dix and the T3 lithograph artists embraced a bold, structured visual language that rendered their subjects as larger-than-life archetypes—most deeply and powerfully through facial expression and subtly contorted or tangled limbs. Just as Dix dissected the psychological realities of his time, the T3 lithographs distilled baseball’s emerging mythology of industrialized heroism into a fine art form—one that blurred the lines between commercial ephemera and avant-garde visual culture, finding in the midst of mechanical reproduction a haunting, lingering humanity.

The T3s as a Precursor to Industrial Fine Art Movements

The key distinction here is not that T3 Turkey Red lithographs surpass Dix, Lautrec, Lissitzky, or other such individual major modernist revolutionaries in singular artistic mastery or clarity of stylistic vision, but rather that they achieve an astonishingly high level of fine art execution at a mass production speed of force, something that was virtually unheard of in handmades at the time.

Handmade Precision on an Industrial Scale

Every T3 lithograph was crafted by skilled artisans, not just mechanically printed.

Chromolithography was an incredibly intricate process, requiring up to 20 stones to render; extensive color separations, hand-alignments, and individual artist touch-ups.

This means that even though they were produced in the thousands, each one was painstakingly built up like a fine art print—far beyond normal commercial printing; the show of force present in individual artist ateliers and avant-garde circles—even the most revolutionary and industrialist.

Sublime Artisanal Execution at the Speed of Modernity

While the works of Dix and Lautrec were individually crafted and had full artistic autonomy, the T3s were designed with an extremely high level of aesthetic and technical integrity—within the confines of mass-production constraints.

Their color layering, textural richness, and lithographic detailing are comparable to the best German, Russian, and French high art lithographic prints of the early 20th century.

No other mass produced commercial print object in America before or after T3s reached this level of high art refinement of the handmade.

The ‘Masterless Masterpieces’ Phenomenon

In a radical break from traditional art historical narratives, the T3 lithographs (along with the American press photographic revolution of the time, spearheaded by figures such as Bain & Thompson) were the result of an industrial workshop of master printmakers.

This makes them one of the only mass-distributed, high-art movements that exist without a single named artist.

In other words, they are masterful despite having no singular “master” behind them—which paradoxically reinforces their significance as a lost fine art movement; furthermore, signifies a deeper revolutionary capacity brought on by the unity of industrialization and high art: the capacity to make beautiful fine art objects as a unit of collaborative efforts at speed. Such a model was theorized broadly by Bauhaus and implemented later at a level of capacity by Warhol’s Factory—but the T3s anticipated and fulfilled this modernist turn decades prior.

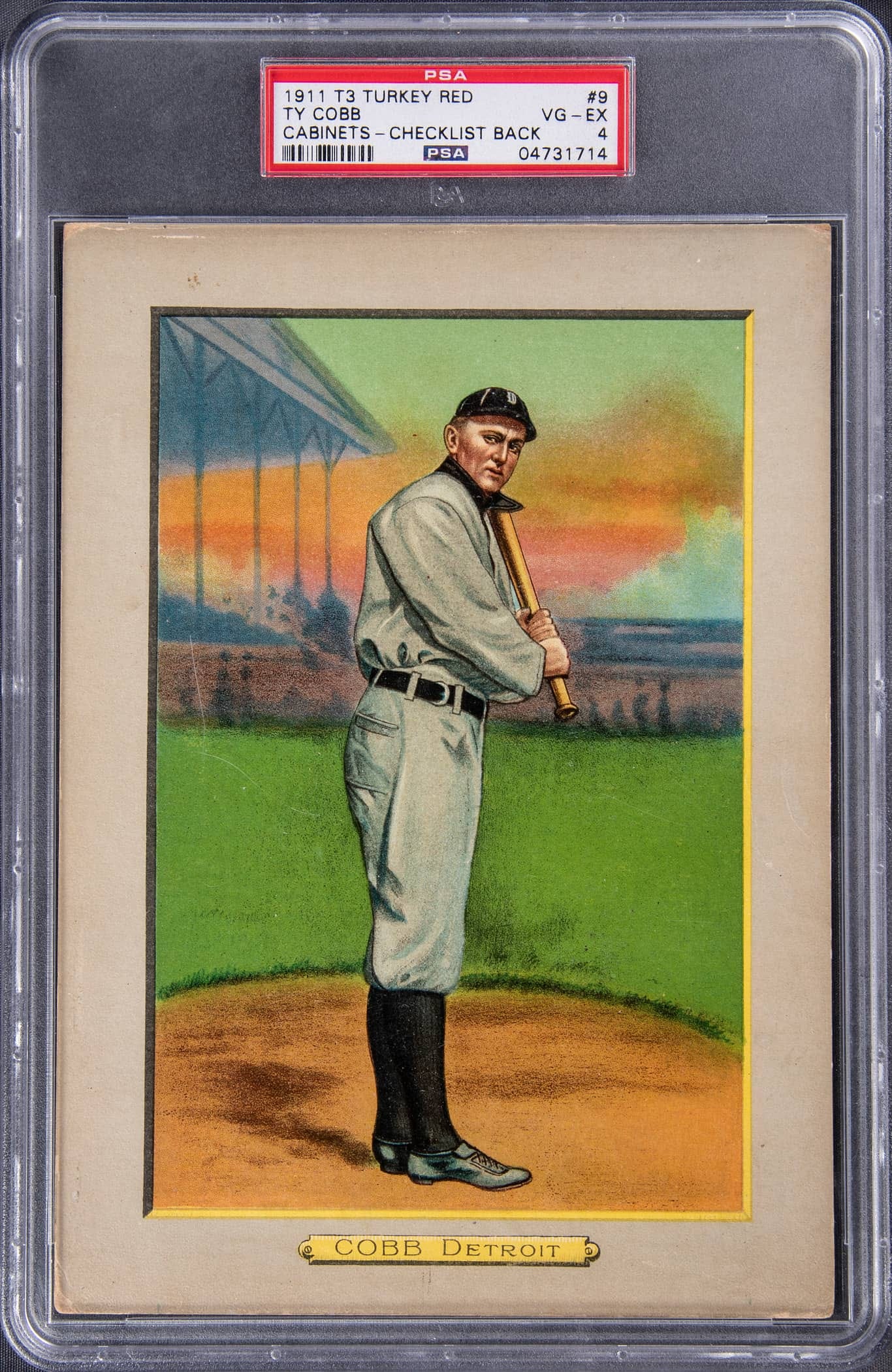

Often regarded as the most sublime realization of the T3 ethos, this lithograph of Ty Cobb embodies the grandeur and intensity of early 20th-century American heroic portraiture. The burning, encroaching sunset and Cobb’s towering, statuesque presence align this work more closely with the monumental tradition of Beaux-Arts painting and neoclassical athletic idealization than with the emerging avant-garde movements of the time.

The T3 series as a whole resists singular stylistic categorization, existing in a state of strange paradox—in large part due to the nature of its production. Its lithographs range from hyper-traditionalist compositions (as seen in Cobb’s commanding figure) to eerily modernist, spectral distortions, as exemplified in Charles Bender’s portrait. Meanwhile, the Vic Willis lithograph—marked by its surreal, Dix-esque mechanized motion and electrified color—pushes further still into the avant-garde, resembling a marionette suspended in a poetic, futuristic dream of metal and technology.

This spectrum of execution—born not from an individual artist’s singular style and hand, but from an anonymous, functionally collaborative collective—reinforces the radical, industrial fine art nature of the set. The T3s did not adhere to any one artistic doctrine; they absorbed many, synthesizing them into something wholly, strikingly, and entirely their own.

1776-1911: A Revolutionary Promise Fulfilled

The full provenance of the American Revolution was both deeply personal and profoundly political—an aesthetic, material, and democratic transformation of what was once considered true, possible, and meaningful, culminating in the political realization of the individual. The T3 Turkey Red lithographs stand as the most complete fulfillment of that revolutionary promise.

They are not just objects; they are proof—proof that fine art, at its most radical and fully realized, is not something to be hoarded, dictated, or enclosed within museums, galleries, or appropriated by elite institutions that limit access. Nor is it to be discharged and delimited by state-controlled ideological programs that censor and direct messaging to create and manipulate desired outcomes. It is something to be owned, lived with, and experienced by the people, in their own spaces, on their own terms.

The founding of America was the founding of a radical promise—the promise of freedom through the sovereignty of the individual: the idea that people—not kings, not aristocrats, not centralized authorities—should hold the power to determine their own lives, their own mythologies, their own art. But this promise has always been contested, resisted, and, in many ways, denied.

The T3 lithographs cut through that resistance and achieved what no other fine art movement did:

They were free fine art—mass-produced but never commodified as luxury goods.

They transcended class—entering homes through a simple exchange system accessible to the many.

They were immediate—they were possessed, touched, pinned to walls, handled, lived with.

They realized what the avant gardes could only theorize—the seamless unity of fine art, industry, and mass ownership.

This was the moment when the revolutionary promise of democratic ownership and the American mythos fully converged. The T3 Turkey Red lithographs were not just industrial fine art—they were the ultimate artifact of American freedom.

This is the real American Revolution, come full circle—not just independence from Britain, not just political democracy, but the full realization of aesthetic and material democracy—the idea that art and culture must belong to everyone.

European, Russian, and even later American movements (Constructivism, Bauhaus, Dada, Pop Art) theorized and reflected upon this in circles that never truly broke with direct impact into the mainstream. The T3s simply did it—perfectly, seamlessly, radically; across all dimensions of their production and distribution—before anyone else could conceive of it.

And then, they were forgotten—not because they failed, but because they succeeded too well. Because they bypassed the museum, the gallery, the art historian, and instead went directly into the hands of the people.

The T3s did not conceptualize revolution—they enacted it. They were not ideology, not propaganda, not an avant-garde experiment, but a lived reality. They prove that America once fully realized its founding promise—and then let it slip away. The T3s did not theorize artistic revolution—they embodied it. They were not speculative manifestos, not propaganda, not an avant-garde experiment—they were the fully realized revolution itself, a living document of the idealistic precepts of America’s political revolution at large. They were not merely an American artistic revolution, they were the American artistic revolution.

To recover the T3s today is not merely to rewrite history—it is to reclaim and honor the very revolutionary promise they fulfilled. It is to restore the missing piece of America’s lost artistic democracy and to demand that fine art—and art itself—be understood not as an elite possession, but as something that fundamentally belongs to the people.

More than that, it is to remember and restore the American artistic and humanitarian legacy of access, ownership, and democracy—a legacy that defines a nation, a world, and a species’ deepest spiritual struggle for self-realization.

De Chirico’s The Disquieting Muses defined an early-century art movement of industrial, modern surrealism in full swing—a global economy and culture jarred into a strange, somnambulistic waking state by the institution of a radical new system: an increasingly interconnected, rapidly accelerating network of goods, services, information, people, and war.

In and through the quaking of the First World War, modern humanist art was forced to reckon with a world operating at a productive, reductive, and mechanized capacity far beyond the comprehension of the primate mind or body.

The artistic movements emergent from this historical unfolding—from the Vic Willis T3 to The Disquieting Muses—reflect an uncanny jarment, a fundamental dislocation from the primary sensorium into an uncertain, unstable, high velocity bullet train of hyper-modernity.